Let My People Go

On July 14, 1978, moments after his brother Anatoly (now Natan) received a thirteen-year sentence for treason, Leonid Shcharansky called across the Moscow courtroom to him: “Tolya! The whole world is with you!” This was something of an exaggeration, but no delusion. The world’s most famous refusenik had a vast base of support, both within and outside the USSR. This could not prevent his conviction on trumped-up charges and his dispatch to the gulag instead of the Jewish State.

How Natan Sharansky (from Shcharansky) and a host of heroic figures like him, emerged from under the rubble of Soviet rule, suffered for their cause, how Jews throughout the world—and many non-Jews as well—rallied around them, and how they ultimately helped liberate Soviet Jewry is the gripping story that Gal Beckerman tells in his thoroughly researched book. It begins in the early 1960s and unfolds mostly on two main stages: the Soviet Union itself and the US. In both places the story is at first one of small clusters of people finding themselves drawn to asserting Jewish identity and solidarity in what seemed to be hopelessly quixotic ways. It ends in the early 1990s with the mass migration of the bulk of the Jews of the former Soviet Union to freedom in Israel and other Western countries. Beckerman’s book is especially welcome in light of the remarkable speed with which the colossal moral struggles of the Cold War are fading from memory.

Behind the scenes, the Israeli government played a crucial role in setting things in motion: its opaquely-named lishka (“bureau”) maintained contacts and provided resources throughout the USSR during the 1950s and early 1960s, utilizing “agricultural attachés” from the Moscow embassy to travel throughout the Soviet Union to “distribute Israeli mementos such as miniature Jewish calendars and Star of David pendants, which were usually handed off in a handshake.” In a country where Jews were constantly reminded of, and often penalized for, their Jewishness but forbidden to express it, these little tokens meant a great deal. Elsewhere, in the Free World, the Israelis were similarly surreptitious but more sophisticated. Among other things, they facilitated the work of a New York-based intellectual, Moshe Decter, whose articles in The New Leader and Foreign Affairs first brought the persecution of Soviet Jews to the attention of journalism and policy elites as well as ordinary citizens. The hope was that they would do what Israel could not risk doing on its own.

But—and this is the heart of the matter—in both the USSR and the US it was the passions and commitments of individuals far removed from elites that really launched the struggle. Within the Soviet Union, Beckerman sees the origins in Latvia, whose period of interwar independence left living memories of vibrant Jewish life. Banding together to construct a Holocaust memorial in a forest outside of Riga where thousands of Jews had been murdered by the Nazis, young Jews developed a sense of identification with their people. In Leningrad, essentially deracinated young Jews, stung by their experience of anti-Semitism, began to prowl around the only remaining synagogue in an effort to find out what it was that made them unacceptably different. They eventually found their way to some of the city’s elderly remaining Zionists and organized new cells of their own. In these and other cities, homespun translations of Leon Uris’ Exodus, “a blockbuster in the samizdat circuit,” provided both a crash course in modern Jewish history and something to dream about.

At roughly the same time, in the US, a Cleveland-based NASA scientist named Lou Rosenblum and his friend Herb Caron, a young assistant professor of psychology, were electrified by their reading of a different book, Ben Hecht’s Perfidy, with its fierce denunciation of world Jewry’s passivity in the face of Nazism. Reading Decter’s articles spurred them to action and in 1963 they created the first grass-roots organization to press both the Jewish establishment and the US government on the issue: the Cleveland Committee on Soviet Anti-Semitism. In New York, a restless British intellectual named Yaakov Birnbaum began to agitate and organize among Orthodox students at Yeshiva University, and then at Columbia, arguing that Soviet Jewry could be their way to channel the gathering revolutionary spirit of the times. He also asked the Hasidic troubadour Shlomo Carlebach, then at the beginning of his musical career, to compose an anthem for the movement, which he did, writing Am Yisrael Chai in a Prague hotel room, wrapped in his tefillin on the morning-after of an ecstatic Purim concert in 1965. Meanwhile, on another plane altogether, Jewish Senators Jacob Javits and Abraham Ribicoff and Justice Arthur Goldberg began to take up the issue, while Abraham Joshua Heschel, haunted by his own narrow prewar escape to America and the placidity he found there, began to exercise his prophetic rhetoric on Soviet Jewry’s behalf.

Emboldened by their overseas supporters, Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War of 1967, and the Soviet regime’s readiness to open a small safety valve of emigration, more and more Soviet Jews began to clamor for permission to leave the USSR. But even though it sometimes opened its country’s doors much more than a crack, the Soviet government was never prepared—until the very end—to allow a truly massive exodus of Jews. Figuring out how to force it to do so became the enduring preoccupation of the fighters for Soviet Jewry everywhere.

Outside the Soviet Union, the activists stuck, for the most part, to conventional and peaceful means of protest, including mass rallies in New York City of up to 200,000 people. Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League assumed a more threatening posture, and even resorted to violence against Soviet missions in the US as well as other targets. Kahane himself may have had nothing to do with the worst of it—the fatal bombing in 1972 of the offices of Sol Hurok, the impresario who had brought the Bolshoi Ballet to America and American artists to the USSR—but this attack deprived him of all credibility and, in Beckerman’s words, “the power to dictate the direction of the Soviet Jewry movement in America.”

This power was exercised, for a crucial few years, by Senator Henry Jackson, the standard-bearer of American liberal anti-Communism, for whom the Soviet Jewish cause exemplified the moral heart of the Cold War—a struggle for basic civil and cultural freedom. At times he promoted the issue more strongly than did the Jewish organizations themselves. In opposition to the wishes of the Nixon Administration, he successfully tied human rights to something that mattered deeply to the Soviets: trade. The passage in 1974 of the bill that he pushed through Congress did not in the end have the desired impact on immigration but it did succeed in putting Soviet Jewry foursquare in the middle of superpower politics.

A year later, the so-called “Third Basket” of the 1975 Helsinki Accords linked acceptance of basic human rights to acceptance of the Soviet order in Europe. The Soviets, concerned above all with trade and solidifying their empire, thought reasonably that the Third Basket’s rhetoric would be no more damaging to their tyranny than the liberal-sounding provisions of their own constitution. Yet the Accords created an opportunity, however small, to at long last hold the Soviets accountable to the universal principles they cynically declaimed, and as Jackson had seized it from above, the dissidents, Jewish and non-Jewish, did so from below.

Sharansky, for one, helped to set up Moscow Helsinki Watch, which put a spotlight not only on the persecution of Jews but on human rights abuses throughout the Soviet Union. His contacts with the Western press and his starring role in a documentary film entitled A Calculated Risk made him both a celebrity and an inevitable target of the Soviet government. But neither his conviction nor his incarceration kept him from continuing to be a thorn in the side of the regime. Even as he was trapped in the gulag, communicating through toilet pipes with Riga’s Yosef Mendelevich and Hillel Butman of Leningrad, who had been imprisoned since their foiled hijacking attempt in 1970, he was making waves overseas. His wife Avital, who had been permitted to emigrate before he became well-known, was conducting an extraordinary world-wide campaign on his behalf. “By the mid-1980s she had made Shcharansky into a household name. For most young people coming of age at the time, the Soviet Jewry movement was Shcharansky. Every Jewish schoolchild could recognize his face.” The witty, cosmopolitan, chess-playing democratic dissident and the newly-Orthodox and kerchiefed, passionate crusader together came to symbolize the two facets of the movement and its romance: a universal struggle for ethical ideals of human rights, and the renewal of Jewish identity in Zionism.

In the 1980s the Soviet regime, increasingly defensive at home and aggressive abroad, and resentful of being nagged about Soviet Jewry by the US government and the court of world public opinion, brutally cracked down on the movement, arresting nearly all of its leaders, and practically halted emigration. “Throughout the second half of 1984, Jewish activists and Hebrew teachers were arrested on all kinds of trumped-up charges-pushing someone, sexual assault, illegal drug possession.” Demoralized and scared, a group of forty refuseniks in Leningrad issued a desperate plea to “the Jews of the West:

You, the sons and daughters of a nation which has suffered the most terrible blows that human madness can inflict, take the truth of the Messiah out of the sheaths of your souls and beat it into the iron will of deeds. Who, if not you, can help us remove the stone from the mouth of the well?

American Jews, above all, kept up the pressure, to which the Reagan administration was highly responsive. But it was only the ascent to power of Mikhail Gorbachev, who sought release from the international isolation in which the Soviet Jewry movement had helped to place the USSR, that made real change possible. Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Shultz, turned out to be as committed a friend as Henry Jackson, even if he spoke in less rousing terms, couching his plea to the Soviets in terms of the realities of the new open societies of the information age. In his first meeting with Gorbachev, he straightforwardly asked if he could take Sharansky and another famous refusenik, Ida Nudel, home with him to the US. This mix of moralism and appeals to mutual interest found a receptive audience in a new generation of Soviet leadership. Materially and ideologically bankrupt, they sought a way out of confrontation and understood, at long last, that Jewish freedom was part of the price.

A brief review can scarcely compass the breadth and richness of Beckerman’s narrative or do justice to the unimaginable physical and moral courage and the resourcefulness of the dissidents and refuseniks crowding his pages. His honest recounting of their human failings and rivalries makes their achievement all the more remarkable. Beckerman also reminds us of the extent to which contemporary American Jewry was shaped by this history. Struggles create leaders and the Soviet Jewry movement was no exception. His book constitutes a veritable who’s who of American Jewish leaders, who early in their professional lives came of age, in one way or another, in the movement: Irving Greenberg, Malcolm Hoenlein, David Harris, Avi Weiss, and Morris Amitay, to name only a few. No less moving is the historical due that Beckerman renders the lesser-known heroes of the movement, such as Glenn Richter of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, and Yuli Kosharovsky, who ran a network of Hebrew teachers throughout the USSR in most dangerous times, and many, many more.

The Soviet Jewry movement was a successful example of the transnational humanitarian advocacy on behalf of persecuted Jews that began in the nineteenth century. It played a substantial role in creating the global concept that today goes by the name of human rights. The movement also illustrates a key feature of the human rights enterprise: the invocation of avowedly universal principles on behalf of very specific groups. A complicated relationship between the universal and the particular lies at the heart of Jewish experience, and accounts for much of the world’s and many Jews’ enduring difficulties in coming to terms with that identity. In the Soviet Jewry movement, this dynamic found an empowering and even healing resolution, at least for a while.

American Jews, once they gained their sea legs, operated here as an advocacy group within a democratic society, one whose identity and ethnic politics spoke in the register of American liberal values. American Jewry is a voluntary community, sustained in no small part by its ability to appeal to moral values, and, as it did in the case of Soviet Jewry, fuse hard power with the romance and ethical pull of the counterculture. Sharansky put it succinctly to a congressional committee in 1986: “Exactly as it was in my case, the final exchange, my final release was reached in quiet diplomacy in exchanging of spies, but as you all understand it, it would never take place if there wasn’t such a strong campaign.”

Toward the end of the book, Beckerman describes the massive rally on the National Mall in December 1987, in which American Jewry came together in a remarkable display of unity and purpose. There was that day a “feeling of collective strength [that] simply would have been impossible twenty-five years before . . . They had come to do something together, and they had done it.” What they had done, through a fractious process that was the exuberant opposite of social engineering and social planning, was grasp the deep political and cultural currents of their times and fashion a new Jewish politics that deftly united the imperatives of physical and cultural survival. Nothing, he notes, has united them in the same way ever since.

Suggested Reading

The Jewish Preview of Books—November 2018

Dozens of books on Jewish history, culture, and literature are published each month. Here are some debuting this November.

The Anti-Imperialism of Idiots

While it is customary to trace the Left’s bitter divorce from Israel to the Six-Day War of 1967, Susie Linfield shows that in some cases the relationship breakdown began earlier, in the late 1950s, when the New Left, having given up faith in the Soviet Union, decided anticolonialism is socialism,

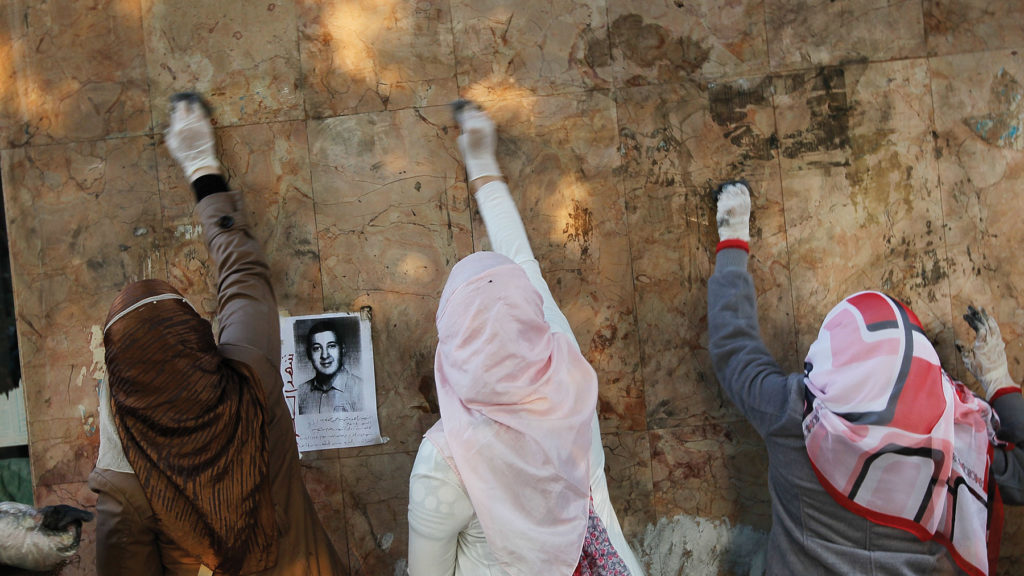

Trashing Dictatorship in Cairo

Tahrir Square isn't the only thing Egypt's democrats need to clean up before democracy takes hold in their country.

Instagramming the Holocaust

This Holocaust Memorial Day, an online project known as Eva’s Stories is uploading snippets of video every 30 minutes to the @eva.stories Instagram page.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In